Beheading: unpleasant but honourable

As it was forbidden to use an executioner’s sword in battle it was regarded more as a tool than a weapon. The executioner was often referred to as the “after-judge” (Nachrichter), as his task started when the judge’s work was complete. Only he was permitted to wield the sword.

Beheading was viewed as an honourable death in comparison to other methods of execution such as hanging, and the family of the condemned person suffered no loss of reputation. As such, this sentence was often passed on those of higher social standing.

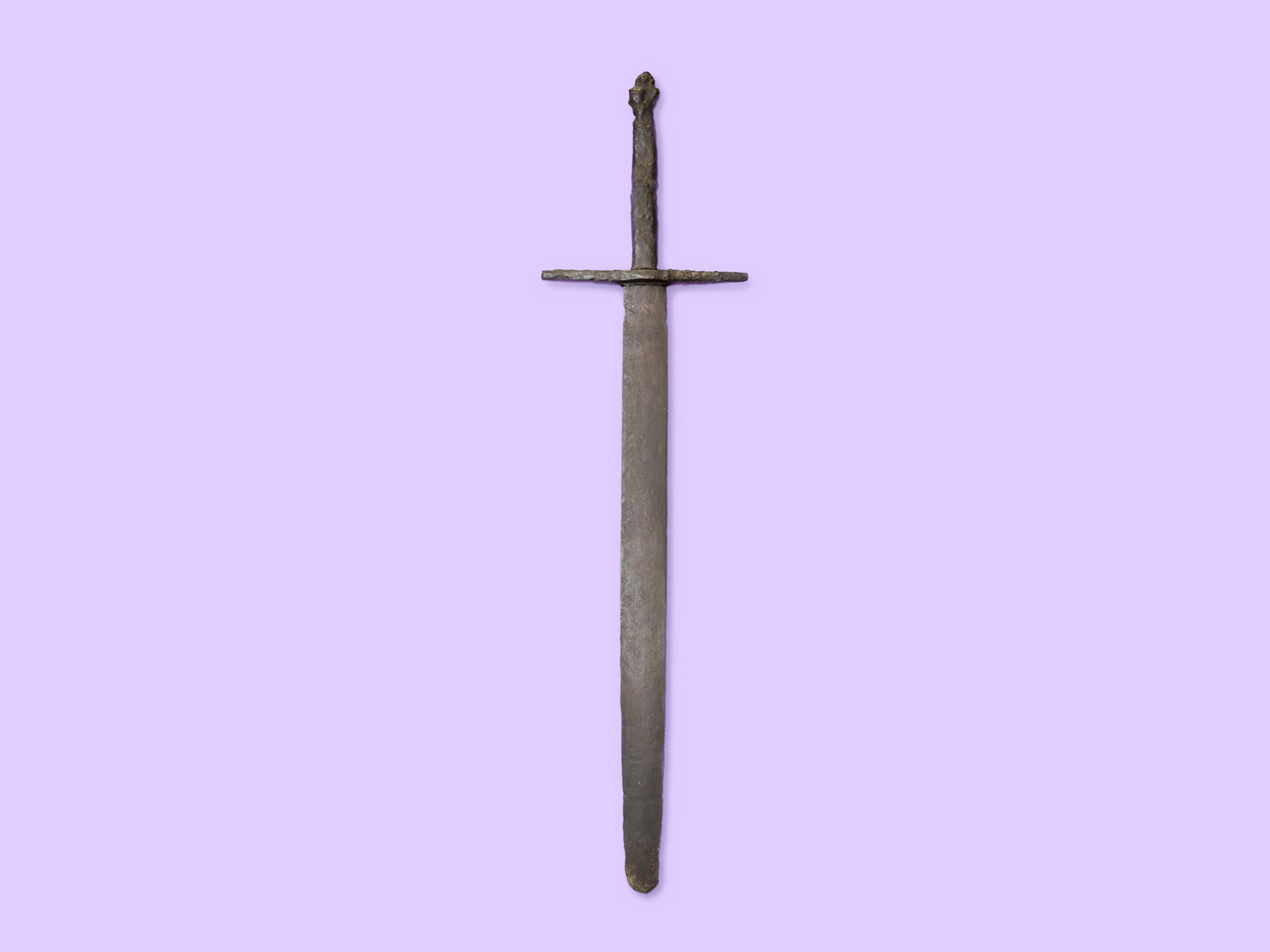

The executioner’s sword on show in the Deutschlandmuseum displays the typical characteristics of this special type of sword: with a broad, flat blade and rounded tip, it is designed to lend itself to ambidextrous use. The rounded tip indicates its status as a “dishonest” weapon which not intended for use in “honest” combat. The sword is 126 mm in length.

A great responsibility yet little honour: the office of executioner

The job of an executioner was demanding. The size and weight of the sword made it difficult to handle and an executioner required not only considerable strength, but a skill borne of long practice. The best results were achieved by striking the neck between the 3rd and 4th cervical vertebrae, thereby severing the head with a single blow. After practicing on animals, executioners were required to pass a final test by performing a clean beheading of a criminal with either sword or axe.

Even though it involved a central social function requiring considerable skill, the profession of executioner was considered dishonourable, and those exercising it experienced considerable social isolation. As a result, the children of executioners were often forced to marry within their own class and sons often had no choice but to follow in their father’s footsteps.

The wages of the executioner were paid by the family of the condemned person. As there were not sufficient death sentences to provide a liveable income, executioners were forced to take on other judicial and penal tasks including torture and corporal punishments, such as the cutting off of a hand. Further income was generated by menial work such as cleaning cesspools and disposing of animal carcasses.

A public execution with a sword in the Middle Ages Book illumination, Chronicles by Jean Froissart, folio 1r, Flanders, early 15th century (source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)

The development of the executioner’s sword

Used up to the 19th century, executioners’ swords were one of the most historically enduring instruments of judicial execution. The executioner’s sword on display in the Deutschlandmuseum is a very early model, with most surviving execution swords dating from the 17th and 18th centuries. Many of these later models bore religious inscriptions or figurative motifs on the blade. No such features are to be found on the sword in the Deutschlandmuseum. Either they never existed or they have been obscured by corrosion.

Execution by sword was eventually phased out from the 18th/19th century, to be replaced by new methods such as the guillotine, which required comparatively little skill or training to operate. Despite this trend, a handful of modern day states still conduct executions with swords.

Property information

Designation

- Date 13th century

- Gallery The High Middle Ages

- Category Weapons

- Origin Germany

- Dimensions 30x126x5 cm (WxHxD)

- Material metal

Property information

Designation

- Datierung 13th century

- Epochenraum The High Middle Ages

- Kategorie Weapons

- Herkunft Germany

- Dimensionen 30x126x5 cm (WxHxD)

- Material metal

About the Deutschlandmuseum

An immersive and innovative experience museum about 2000 years of German history

Reading tips and links

Lifesaver? The German Steel Helmet in the First World War

German Tank Museum Munster

Lifesaver? The German Steel Helmet in the First World War

German Tank Museum Munster

Share article

Other objects in this collection

Discover history

Visit the unique Deutschlandmuseum and experience immersive history

2000 Jahre

12 Epochen

1 Stunde